/*!

An SPMC channel with low, consistent latency, designed for cases where values arrive in a batch and

must be processed now-or-never.

burst-pool differs from a regular spmc channel in one major way: **sending fails when all workers

are currently busy**. This lets the sender distribute as much work as possible, and then handle

overflow work differently (probably by throwing it away).

## Performance

**tl;dr:** Same ballpark as [spmc]. Best when the number of workers is less than number of cores.

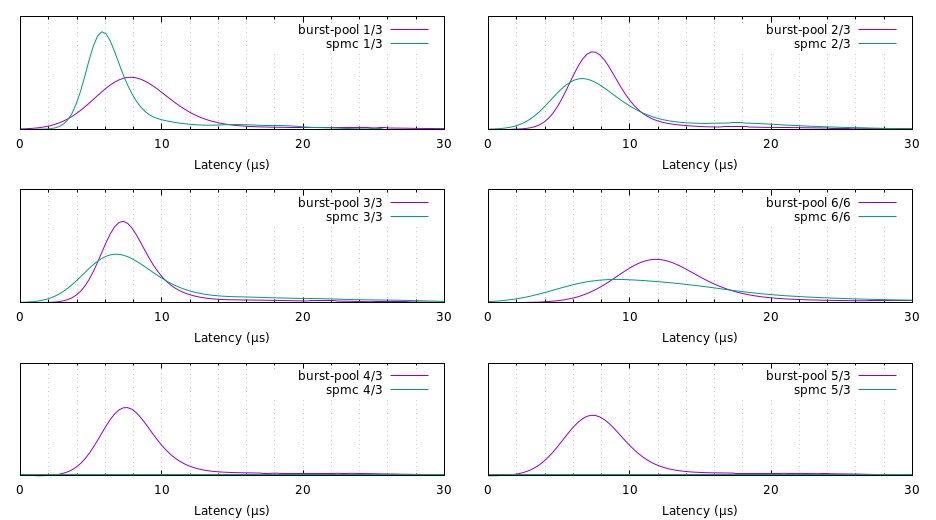

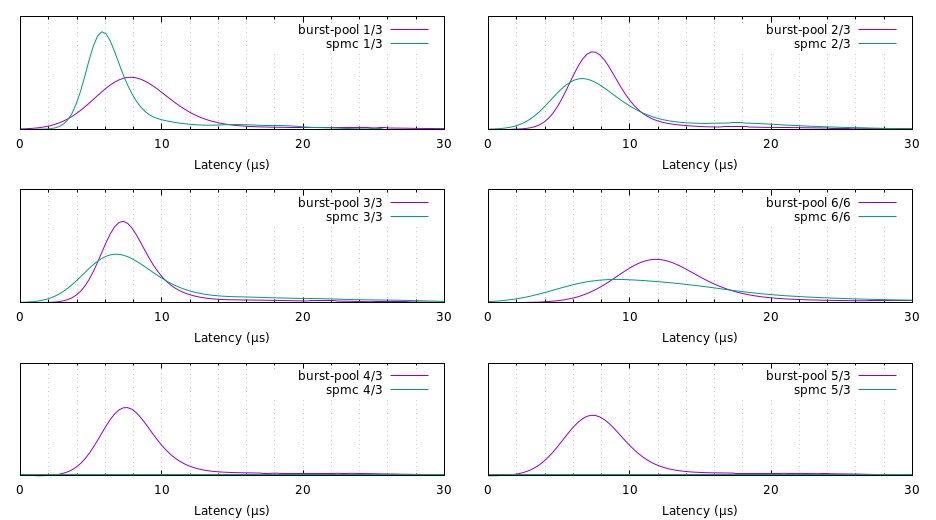

I'm using the excellent [spmc] crate as a benchmark. spmc provides a reliable unbounded channel,

and when the pool is overloaded it has the normal "queueing" semantics (as opposed to burst-pool's

"return-to-sender" semantics). The metric we care about is `enqueue`→`recv` latency. Below are

some kernel density estimates. The "n/m" notation in the labels means "n messages sent to m

workers".

[spmc]: https://docs.rs/spmc

Here's my interpretation of the numbers:

* Keeping the number of workers fixed to 3 and varying the number of messages sent appears to have

no effect on burst-pool's performance. spmc, on the other hand, compares favourably when pool

utilisation is low (1/3), becoming gradually worse as the number of messages increases (2/3),

until it is roughly the same as burst-pool in the saturating case (3/3).

* When the pool is overloaded (4/3, 5/3) we see the difference in the semantics of the two crates.

In the burst-pool benchmark, only 3 messages are sent and 2 are discarded. In the spmc benchmark,

all 5 messages are sent, giving a bimodal distribution with the second peak around 1000 μs. (This

seems to mess up gnuplot.)

* Comparing the two saturating benchmarks (3/3, 6/6) we see another difference. When the number of

workers is less than the number of available cores (3/3) we see that performance is roughly the

same, but that burst-pool degrades more badly when it exceeds the number of cores (6/6).

* The response time is generally a bit more reliable for burst-pool than spmc (ie. the variance is

lower), with the exception of the 1/3 benchmark.

These observations are consistent with the expected performance characteristics. (See

[Design](#design), below.)

Run `cargo bench` to make some measurements on your own machine; there's also a gnuplot script

which you can use to visualise the results. (Pro tip: If your results are significantly worse than

those above, your kernel might be powering down CPU cores too eagerly. If you care about latency

more than battery life, consider setting max_cstate = 0.)

## Usage

The API requires two calls to actually send a message to a receiver: first you place your message

in the mailbox of one of your workers (`enqueue`); then you wake the worker up, notifying it that

it should check its mailbox (`wake_all`). A call to `enqueue` will only succeed if the sender can

find an empty mailbox to put the message in (ie., at least one of your workers must currently be

blocking on a call to `recv`). If `enqueue` fails, you get your message back. If it succeeds, the

message will be recieved by exactly one receiver the next time you call `wake_all`.

```

# use burst_pool::*;

#

# fn sleep_ms(x: u64) {

# std::thread::sleep(std::time::Duration::from_millis(x));

# }

#

// Create a handle for sending strings

let mut sender: Sender = Sender::new();

// Create a handle for receiving strings, and pass it off to a worker thread.

// Repeat this step as necessary.

let mut receiver: Receiver = sender.mk_receiver();

let th = std::thread::spawn(move ||

loop {

let x = receiver.recv().unwrap();

println!("{}", x);

}

);

// Give the worker thread some time to spawn

sleep_ms(10);

// Send a string to the worker and unblock it

sender.enqueue(Box::new(String::from("hello")));

sender.wake_all();

sleep_ms(10); // wait for it to process the first string

// Send another string

sender.enqueue(Box::new(String::from("world!")));

sender.wake_all();

sleep_ms(10);

// Drop the send handle, signalling the worker to shutdown

std::mem::drop(sender);

th.join().unwrap_err(); // RecvError::Orphaned

```

## Design

Each receiver has a "slot" which is either empty, blocked, or contains a pointer to some work.

Whenever a receiver's slot is empty, it goes to sleep by polling an eventfd. When issuing work,

the sender goes through the slots round-robin, placing work in the empty ones. It then signals the

eventfd, waking up all sleeping receivers. If a receiver wakes up and finds work in its slot, it

takes the work and blocks its slot. If a receivers wakes up and finds its slot is still empty, it

goes back to sleep. When a receiver has finished processing the work, it unblocks its slot.

This design means that we expect `enqueue`→`recv` latencies to be independent of the number of

payloads sent. However, we expect it to become much worse as soon as there are more worker threads

than cores available. The benchmark results are consistent with these expectations.

## Portability

This crate is Linux-only.

*/

/*

2 payloads sent to 3 workers | 1% | 10% | 50% | 90% | 99% | mean | stddev

----- | ---: | ---: | ----: | ------: | ------: | -----: | -----:

burst_chan | 3897 | 5144 | 8181 | 22370 | 31162 | 12146 | 31760

spmc | 4260 | 5454 | 7279 | 14389 | 30019 | 9169 | 8484

3 payloads sent to 3 workers | 1% | 10% | 50% | 90% | 99% | mean | stddev

----- | ---: | ---: | ----: | ------: | ------: | -----: | -----:

burst_chan | 4162 | 5116 | 8165 | 22000 | 35767 | 11565 | 14096

spmc | 3911 | 5454 | 8895 | 23216 | 61595 | 12102 | 10197

5 payloads sent to 3 workers | 1% | 10% | 50% | 90% | 99% | mean | stddev

----- | ---: | ---: | ----: | ------: | ------: | -----: | -----:

burst_chan | 3773 | 4786 | 8724 | 22877 | 34214 | 12091 | 10276

spmc | 4241 | 5931 | 12542 | 1064532 | 1086586 | 432018 | 516410

6 payloads sent to 6 workers | 1% | 10% | 50% | 90% | 99% | mean | stddev

----- | ---: | ---: | ----: | ------: | ------: | -----: | -----:

burst_chan | 5875 | 7344 | 12265 | 30397 | 47118 | 15984 | 10130

spmc | 4170 | 7050 | 14561 | 34644 | 59763 | 18003 | 12511

*/

extern crate nix;

extern crate byteorder;

use byteorder::*;

use nix::sys::eventfd::*;

use nix::unistd::*;

use std::os::unix::io::RawFd;

use std::ptr;

use std::thread;

use std::sync::atomic::*;

use std::sync::Arc;

use nix::poll::*;

pub struct Sender {

eventfd: RawFd,

workers: Vec>>,

next_worker: usize,

workers_to_unblock: i64,

eventfd_buf: [u8; 8],

}

pub struct Receiver {

inner: Arc>,

eventfd: RawFd,

eventfd_buf: [u8; 8],

}

unsafe impl Send for Sender {}

unsafe impl Send for Receiver {}

struct Worker {

state: AtomicUsize,

slot: AtomicPtr,

}

// Receiver states

const RS_WAITING: usize = 0; // This receiver has no work to do, and is blocking

const RS_PENDING: usize = 1; // This receiver has work to do, but hasn't unblocked yet

const RS_RUNNING: usize = 2; // This receiver is running and is doing some work

const RS_ORPHANED: usize = 3; // The sender has gone away, never to return

// TODO: const RS_INTEND_TO_DROP // The receiver wants to be dropped from the pool

impl Sender {

pub fn new() -> Sender {

Sender {

eventfd: eventfd(0, EFD_SEMAPHORE).unwrap(),

workers: vec![],

next_worker: 0,

workers_to_unblock: 0,

eventfd_buf: [0;8],

}

}

/// Create a new receiver handle.

pub fn mk_receiver(&mut self) -> Receiver {

let worker = Arc::new(Worker {

state: AtomicUsize::new(RS_RUNNING),

slot: AtomicPtr::new(ptr::null_mut()),

});

self.workers.push(worker.clone());

Receiver {

inner: worker,

eventfd: self.eventfd,

eventfd_buf: [0; 8],

}

}

/// Wake up *all* reciever threads.

///

/// This function is guaranteed to wake up all the threads. If some threads are already

/// running, then those threads, or others, may be woken up spuriously in the future as a

/// result.

///

/// This function does not block, but it does make a (single) syscall.

pub fn wake_all(&mut self) {

NativeEndian::write_i64(&mut self.eventfd_buf[..], self.workers_to_unblock);

self.workers_to_unblock = 0;

write(self.eventfd, &self.eventfd_buf).unwrap();

}

}

impl Sender {

/// Attempt to send a payload to a waiting receiver.

///

/// `enqueue` will only succeed if there is a receiver ready to take the value *right now*. If no

/// receivers are ready, the value is returned-to-sender.

///

/// Note: `enqueue` will **not** unblock the receiver it sends the payload to. You must call

/// `wake_all` after calling `enqueue`!

///

/// This function does not block or make any syscalls.

pub fn enqueue(&mut self, x: Box) -> Option> {

// 1. Find a receiver in WAITING state

// 2. Write ptr to that receiver's slot

// 3. Set that receiver to PENDING state

// 4. Note that we need to increment eventfd

let mut target_worker = None;

for i in 0..self.workers.len() {

let i2 = (i + self.next_worker) % self.workers.len();

match self.workers[i2].state.compare_and_swap(RS_WAITING, RS_PENDING, Ordering::SeqCst) {

RS_WAITING => {

/* it was ready */

target_worker = Some(i2);

break;

}

RS_PENDING | RS_RUNNING => { /* it's busy */ }

x => panic!("enqueue: bad state ({}). Please report this error.", x),

}

}

match target_worker {

Some(i) => {

let ptr = self.workers[i].slot.swap(Box::into_raw(x), Ordering::SeqCst);

assert!(ptr.is_null(), "enqueue: slot contains non-null ptr. Please report this error.");

self.next_worker = (i + 1) % self.workers.len();

self.workers_to_unblock += 1;

None

}

None => Some(x)

}

}

}

impl Receiver {

/// Blocks until (1) a message is sent to this `Receiver`, and (2) wake_all() is called on the

/// associated `Sender`.

pub fn recv(&mut self) -> Result, RecvError> {

// 1. Set state to WAITING

// 2. Block on eventfd

// 3. Check state to make sure it's PENDING

// 4. If so, change state to RUNNING

// 5. Decrement the eventfd

// 6. Take ptr from slot and return

// This function always leaves the state as RUNNING or ORPHANED.

// The sender is allowed to (A) swap the state from WAITING to PENDING, and (B) set the

// state to ORPHANED.

// Therefore, when entering this function, the state must be RUNNING or ORPHANED.

match self.inner.state.compare_and_swap(RS_RUNNING, RS_WAITING, Ordering::SeqCst) {

RS_RUNNING => { /* things looks good. onward! */ }

RS_ORPHANED => { return Err(RecvError::Orphaned); }

x => panic!("recv::1: bad state ({}). Please report this error.", x),

}

let mut pollfds = [PollFd::new(self.eventfd, POLLIN)];

loop {

// Block until eventfd becomes non-zero

poll(&mut pollfds, -1).unwrap();

match self.inner.state.compare_and_swap(RS_PENDING, RS_RUNNING, Ordering::SeqCst) {

RS_PENDING => /* this was a genuine wakeup. let's do some work! */ break,

RS_WAITING =>

// A wakeup was sent, but it was intended for someone else. First, we let the

// other threads check if the wakeup was for them...

thread::yield_now(),

// ...and now we go back to blocking on eventfd

RS_ORPHANED => return Err(RecvError::Orphaned),

x => panic!("recv::2: bad state ({}). Please report this error.", x),

}

}

// Decrement the eventfd to show that one of the inteded workers got the message.

// FIXME: This additional syscall is quite painful :-(

read(self.eventfd, &mut self.eventfd_buf).unwrap();

let ptr = self.inner.slot.swap(ptr::null_mut(), Ordering::SeqCst);

assert!(!ptr.is_null(), "recv: slot contains null ptr. Please report this error.");

unsafe { Ok(Box::from_raw(ptr)) }

}

}

impl Drop for Sender {

/// All receivers will unblock with `RecvError::Orphaned`.

fn drop(&mut self) {

// Inform the receivers that the sender is going away.

for w in self.workers.iter_mut() {

w.state.store(RS_ORPHANED, Ordering::SeqCst);

}

NativeEndian::write_i64(&mut self.eventfd_buf[..], 1);

write(self.eventfd, &self.eventfd_buf).unwrap();

}

}

#[derive(Debug, PartialEq)]

pub enum RecvError {

Orphaned,

}

#[cfg(test)]

mod tests {

}

Here's my interpretation of the numbers:

* Keeping the number of workers fixed to 3 and varying the number of messages sent appears to have

no effect on burst-pool's performance. spmc, on the other hand, compares favourably when pool

utilisation is low (1/3), becoming gradually worse as the number of messages increases (2/3),

until it is roughly the same as burst-pool in the saturating case (3/3).

* When the pool is overloaded (4/3, 5/3) we see the difference in the semantics of the two crates.

In the burst-pool benchmark, only 3 messages are sent and 2 are discarded. In the spmc benchmark,

all 5 messages are sent, giving a bimodal distribution with the second peak around 1000 μs. (This

seems to mess up gnuplot.)

* Comparing the two saturating benchmarks (3/3, 6/6) we see another difference. When the number of

workers is less than the number of available cores (3/3) we see that performance is roughly the

same, but that burst-pool degrades more badly when it exceeds the number of cores (6/6).

* The response time is generally a bit more reliable for burst-pool than spmc (ie. the variance is

lower), with the exception of the 1/3 benchmark.

These observations are consistent with the expected performance characteristics. (See

[Design](#design), below.)

Run `cargo bench` to make some measurements on your own machine; there's also a gnuplot script

which you can use to visualise the results. (Pro tip: If your results are significantly worse than

those above, your kernel might be powering down CPU cores too eagerly. If you care about latency

more than battery life, consider setting max_cstate = 0.)

## Usage

The API requires two calls to actually send a message to a receiver: first you place your message

in the mailbox of one of your workers (`enqueue`); then you wake the worker up, notifying it that

it should check its mailbox (`wake_all`). A call to `enqueue` will only succeed if the sender can

find an empty mailbox to put the message in (ie., at least one of your workers must currently be

blocking on a call to `recv`). If `enqueue` fails, you get your message back. If it succeeds, the

message will be recieved by exactly one receiver the next time you call `wake_all`.

```

# use burst_pool::*;

#

# fn sleep_ms(x: u64) {

# std::thread::sleep(std::time::Duration::from_millis(x));

# }

#

// Create a handle for sending strings

let mut sender: Sender = Sender::new();

// Create a handle for receiving strings, and pass it off to a worker thread.

// Repeat this step as necessary.

let mut receiver: Receiver = sender.mk_receiver();

let th = std::thread::spawn(move ||

loop {

let x = receiver.recv().unwrap();

println!("{}", x);

}

);

// Give the worker thread some time to spawn

sleep_ms(10);

// Send a string to the worker and unblock it

sender.enqueue(Box::new(String::from("hello")));

sender.wake_all();

sleep_ms(10); // wait for it to process the first string

// Send another string

sender.enqueue(Box::new(String::from("world!")));

sender.wake_all();

sleep_ms(10);

// Drop the send handle, signalling the worker to shutdown

std::mem::drop(sender);

th.join().unwrap_err(); // RecvError::Orphaned

```

## Design

Each receiver has a "slot" which is either empty, blocked, or contains a pointer to some work.

Whenever a receiver's slot is empty, it goes to sleep by polling an eventfd. When issuing work,

the sender goes through the slots round-robin, placing work in the empty ones. It then signals the

eventfd, waking up all sleeping receivers. If a receiver wakes up and finds work in its slot, it

takes the work and blocks its slot. If a receivers wakes up and finds its slot is still empty, it

goes back to sleep. When a receiver has finished processing the work, it unblocks its slot.

This design means that we expect `enqueue`→`recv` latencies to be independent of the number of

payloads sent. However, we expect it to become much worse as soon as there are more worker threads

than cores available. The benchmark results are consistent with these expectations.

## Portability

This crate is Linux-only.

*/

/*

2 payloads sent to 3 workers | 1% | 10% | 50% | 90% | 99% | mean | stddev

----- | ---: | ---: | ----: | ------: | ------: | -----: | -----:

burst_chan | 3897 | 5144 | 8181 | 22370 | 31162 | 12146 | 31760

spmc | 4260 | 5454 | 7279 | 14389 | 30019 | 9169 | 8484

3 payloads sent to 3 workers | 1% | 10% | 50% | 90% | 99% | mean | stddev

----- | ---: | ---: | ----: | ------: | ------: | -----: | -----:

burst_chan | 4162 | 5116 | 8165 | 22000 | 35767 | 11565 | 14096

spmc | 3911 | 5454 | 8895 | 23216 | 61595 | 12102 | 10197

5 payloads sent to 3 workers | 1% | 10% | 50% | 90% | 99% | mean | stddev

----- | ---: | ---: | ----: | ------: | ------: | -----: | -----:

burst_chan | 3773 | 4786 | 8724 | 22877 | 34214 | 12091 | 10276

spmc | 4241 | 5931 | 12542 | 1064532 | 1086586 | 432018 | 516410

6 payloads sent to 6 workers | 1% | 10% | 50% | 90% | 99% | mean | stddev

----- | ---: | ---: | ----: | ------: | ------: | -----: | -----:

burst_chan | 5875 | 7344 | 12265 | 30397 | 47118 | 15984 | 10130

spmc | 4170 | 7050 | 14561 | 34644 | 59763 | 18003 | 12511

*/

extern crate nix;

extern crate byteorder;

use byteorder::*;

use nix::sys::eventfd::*;

use nix::unistd::*;

use std::os::unix::io::RawFd;

use std::ptr;

use std::thread;

use std::sync::atomic::*;

use std::sync::Arc;

use nix::poll::*;

pub struct Sender {

eventfd: RawFd,

workers: Vec>>,

next_worker: usize,

workers_to_unblock: i64,

eventfd_buf: [u8; 8],

}

pub struct Receiver {

inner: Arc>,

eventfd: RawFd,

eventfd_buf: [u8; 8],

}

unsafe impl Send for Sender {}

unsafe impl Send for Receiver {}

struct Worker {

state: AtomicUsize,

slot: AtomicPtr,

}

// Receiver states

const RS_WAITING: usize = 0; // This receiver has no work to do, and is blocking

const RS_PENDING: usize = 1; // This receiver has work to do, but hasn't unblocked yet

const RS_RUNNING: usize = 2; // This receiver is running and is doing some work

const RS_ORPHANED: usize = 3; // The sender has gone away, never to return

// TODO: const RS_INTEND_TO_DROP // The receiver wants to be dropped from the pool

impl Sender {

pub fn new() -> Sender {

Sender {

eventfd: eventfd(0, EFD_SEMAPHORE).unwrap(),

workers: vec![],

next_worker: 0,

workers_to_unblock: 0,

eventfd_buf: [0;8],

}

}

/// Create a new receiver handle.

pub fn mk_receiver(&mut self) -> Receiver {

let worker = Arc::new(Worker {

state: AtomicUsize::new(RS_RUNNING),

slot: AtomicPtr::new(ptr::null_mut()),

});

self.workers.push(worker.clone());

Receiver {

inner: worker,

eventfd: self.eventfd,

eventfd_buf: [0; 8],

}

}

/// Wake up *all* reciever threads.

///

/// This function is guaranteed to wake up all the threads. If some threads are already

/// running, then those threads, or others, may be woken up spuriously in the future as a

/// result.

///

/// This function does not block, but it does make a (single) syscall.

pub fn wake_all(&mut self) {

NativeEndian::write_i64(&mut self.eventfd_buf[..], self.workers_to_unblock);

self.workers_to_unblock = 0;

write(self.eventfd, &self.eventfd_buf).unwrap();

}

}

impl Sender {

/// Attempt to send a payload to a waiting receiver.

///

/// `enqueue` will only succeed if there is a receiver ready to take the value *right now*. If no

/// receivers are ready, the value is returned-to-sender.

///

/// Note: `enqueue` will **not** unblock the receiver it sends the payload to. You must call

/// `wake_all` after calling `enqueue`!

///

/// This function does not block or make any syscalls.

pub fn enqueue(&mut self, x: Box) -> Option> {

// 1. Find a receiver in WAITING state

// 2. Write ptr to that receiver's slot

// 3. Set that receiver to PENDING state

// 4. Note that we need to increment eventfd

let mut target_worker = None;

for i in 0..self.workers.len() {

let i2 = (i + self.next_worker) % self.workers.len();

match self.workers[i2].state.compare_and_swap(RS_WAITING, RS_PENDING, Ordering::SeqCst) {

RS_WAITING => {

/* it was ready */

target_worker = Some(i2);

break;

}

RS_PENDING | RS_RUNNING => { /* it's busy */ }

x => panic!("enqueue: bad state ({}). Please report this error.", x),

}

}

match target_worker {

Some(i) => {

let ptr = self.workers[i].slot.swap(Box::into_raw(x), Ordering::SeqCst);

assert!(ptr.is_null(), "enqueue: slot contains non-null ptr. Please report this error.");

self.next_worker = (i + 1) % self.workers.len();

self.workers_to_unblock += 1;

None

}

None => Some(x)

}

}

}

impl Receiver {

/// Blocks until (1) a message is sent to this `Receiver`, and (2) wake_all() is called on the

/// associated `Sender`.

pub fn recv(&mut self) -> Result, RecvError> {

// 1. Set state to WAITING

// 2. Block on eventfd

// 3. Check state to make sure it's PENDING

// 4. If so, change state to RUNNING

// 5. Decrement the eventfd

// 6. Take ptr from slot and return

// This function always leaves the state as RUNNING or ORPHANED.

// The sender is allowed to (A) swap the state from WAITING to PENDING, and (B) set the

// state to ORPHANED.

// Therefore, when entering this function, the state must be RUNNING or ORPHANED.

match self.inner.state.compare_and_swap(RS_RUNNING, RS_WAITING, Ordering::SeqCst) {

RS_RUNNING => { /* things looks good. onward! */ }

RS_ORPHANED => { return Err(RecvError::Orphaned); }

x => panic!("recv::1: bad state ({}). Please report this error.", x),

}

let mut pollfds = [PollFd::new(self.eventfd, POLLIN)];

loop {

// Block until eventfd becomes non-zero

poll(&mut pollfds, -1).unwrap();

match self.inner.state.compare_and_swap(RS_PENDING, RS_RUNNING, Ordering::SeqCst) {

RS_PENDING => /* this was a genuine wakeup. let's do some work! */ break,

RS_WAITING =>

// A wakeup was sent, but it was intended for someone else. First, we let the

// other threads check if the wakeup was for them...

thread::yield_now(),

// ...and now we go back to blocking on eventfd

RS_ORPHANED => return Err(RecvError::Orphaned),

x => panic!("recv::2: bad state ({}). Please report this error.", x),

}

}

// Decrement the eventfd to show that one of the inteded workers got the message.

// FIXME: This additional syscall is quite painful :-(

read(self.eventfd, &mut self.eventfd_buf).unwrap();

let ptr = self.inner.slot.swap(ptr::null_mut(), Ordering::SeqCst);

assert!(!ptr.is_null(), "recv: slot contains null ptr. Please report this error.");

unsafe { Ok(Box::from_raw(ptr)) }

}

}

impl Drop for Sender {

/// All receivers will unblock with `RecvError::Orphaned`.

fn drop(&mut self) {

// Inform the receivers that the sender is going away.

for w in self.workers.iter_mut() {

w.state.store(RS_ORPHANED, Ordering::SeqCst);

}

NativeEndian::write_i64(&mut self.eventfd_buf[..], 1);

write(self.eventfd, &self.eventfd_buf).unwrap();

}

}

#[derive(Debug, PartialEq)]

pub enum RecvError {

Orphaned,

}

#[cfg(test)]

mod tests {

}

Here's my interpretation of the numbers:

* Keeping the number of workers fixed to 3 and varying the number of messages sent appears to have

no effect on burst-pool's performance. spmc, on the other hand, compares favourably when pool

utilisation is low (1/3), becoming gradually worse as the number of messages increases (2/3),

until it is roughly the same as burst-pool in the saturating case (3/3).

* When the pool is overloaded (4/3, 5/3) we see the difference in the semantics of the two crates.

In the burst-pool benchmark, only 3 messages are sent and 2 are discarded. In the spmc benchmark,

all 5 messages are sent, giving a bimodal distribution with the second peak around 1000 μs. (This

seems to mess up gnuplot.)

* Comparing the two saturating benchmarks (3/3, 6/6) we see another difference. When the number of

workers is less than the number of available cores (3/3) we see that performance is roughly the

same, but that burst-pool degrades more badly when it exceeds the number of cores (6/6).

* The response time is generally a bit more reliable for burst-pool than spmc (ie. the variance is

lower), with the exception of the 1/3 benchmark.

These observations are consistent with the expected performance characteristics. (See

[Design](#design), below.)

Run `cargo bench` to make some measurements on your own machine; there's also a gnuplot script

which you can use to visualise the results. (Pro tip: If your results are significantly worse than

those above, your kernel might be powering down CPU cores too eagerly. If you care about latency

more than battery life, consider setting max_cstate = 0.)

## Usage

The API requires two calls to actually send a message to a receiver: first you place your message

in the mailbox of one of your workers (`enqueue`); then you wake the worker up, notifying it that

it should check its mailbox (`wake_all`). A call to `enqueue` will only succeed if the sender can

find an empty mailbox to put the message in (ie., at least one of your workers must currently be

blocking on a call to `recv`). If `enqueue` fails, you get your message back. If it succeeds, the

message will be recieved by exactly one receiver the next time you call `wake_all`.

```

# use burst_pool::*;

#

# fn sleep_ms(x: u64) {

# std::thread::sleep(std::time::Duration::from_millis(x));

# }

#

// Create a handle for sending strings

let mut sender: Sender

Here's my interpretation of the numbers:

* Keeping the number of workers fixed to 3 and varying the number of messages sent appears to have

no effect on burst-pool's performance. spmc, on the other hand, compares favourably when pool

utilisation is low (1/3), becoming gradually worse as the number of messages increases (2/3),

until it is roughly the same as burst-pool in the saturating case (3/3).

* When the pool is overloaded (4/3, 5/3) we see the difference in the semantics of the two crates.

In the burst-pool benchmark, only 3 messages are sent and 2 are discarded. In the spmc benchmark,

all 5 messages are sent, giving a bimodal distribution with the second peak around 1000 μs. (This

seems to mess up gnuplot.)

* Comparing the two saturating benchmarks (3/3, 6/6) we see another difference. When the number of

workers is less than the number of available cores (3/3) we see that performance is roughly the

same, but that burst-pool degrades more badly when it exceeds the number of cores (6/6).

* The response time is generally a bit more reliable for burst-pool than spmc (ie. the variance is

lower), with the exception of the 1/3 benchmark.

These observations are consistent with the expected performance characteristics. (See

[Design](#design), below.)

Run `cargo bench` to make some measurements on your own machine; there's also a gnuplot script

which you can use to visualise the results. (Pro tip: If your results are significantly worse than

those above, your kernel might be powering down CPU cores too eagerly. If you care about latency

more than battery life, consider setting max_cstate = 0.)

## Usage

The API requires two calls to actually send a message to a receiver: first you place your message

in the mailbox of one of your workers (`enqueue`); then you wake the worker up, notifying it that

it should check its mailbox (`wake_all`). A call to `enqueue` will only succeed if the sender can

find an empty mailbox to put the message in (ie., at least one of your workers must currently be

blocking on a call to `recv`). If `enqueue` fails, you get your message back. If it succeeds, the

message will be recieved by exactly one receiver the next time you call `wake_all`.

```

# use burst_pool::*;

#

# fn sleep_ms(x: u64) {

# std::thread::sleep(std::time::Duration::from_millis(x));

# }

#

// Create a handle for sending strings

let mut sender: Sender