bytesbuf

| Crates.io | bytesbuf |

| lib.rs | bytesbuf |

| version | 0.2.2 |

| created_at | 2025-12-10 13:11:37.675451+00 |

| updated_at | 2026-01-15 09:27:28.076575+00 |

| description | Types for creating and manipulating byte sequences. |

| homepage | https://github.com/microsoft/oxidizer |

| repository | https://github.com/microsoft/oxidizer |

| max_upload_size | |

| id | 1977959 |

| size | 510,429 |

documentation

README

Types for creating and manipulating byte sequences.

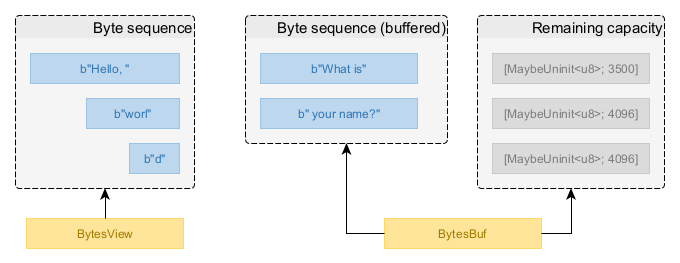

Types in this crate enable you to operate on logical sequences of bytes stored in memory,

similar to a &[u8] but with some key differences:

- The bytes in a byte sequence are not required to be consecutive in memory.

- The bytes in a byte sequence are always immutable (append-only construction).

In practical terms, you may think of a byte sequence as a Vec<Vec<u8>> whose contents are

treated as one logical sequence of bytes. Byte sequences are created via BytesBuf and

consumed via BytesView.

The primary motivation for using byte sequences instead of simple byte slices is to enable high-performance zero-copy I/O APIs to produce and consume byte sequences with minimal overhead.

Consuming Byte Sequences

A byte sequence is typically consumed by reading its contents from the start. This is done via the

BytesView type, which is a view over a byte sequence. When reading data, the bytes read are

removed from the front of the view, shrinking it to only the remaining bytes.

There are many helper methods on this type for easily consuming bytes from the view:

get_num_le::<T>()reads numbers. Big-endian/native-endian variants also exist.get_byte()reads a single byte.copy_to_slice()copies bytes into a provided slice.copy_to_uninit_slice()copies bytes into a provided uninitialized slice.as_read()creates astd::io::Readadapter for reading bytes from the view.

use bytesbuf::BytesView;

fn consume_message(mut message: BytesView) {

// We read the message and calculate the sum of all the words in it.

let mut sum: u64 = 0;

while !message.is_empty() {

let word = message.get_num_le::<u64>();

sum = sum.saturating_add(word);

}

println!("Message received. The sum of all words in the message is {sum}.");

}

If the helper methods are not sufficient, you can access the byte sequence behind the BytesView

via byte slices using the following fundamental methods that underpin the convenience methods:

first_slice()returns the first slice of bytes that makes up the byte sequence. The length of this slice is determined by the memory layout of the byte sequence and the first slice may not contain all the bytes.advance()marks bytes from the beginning offirst_slice()as read, shrinking the view by the corresponding amount and moving remaining data up to the front. When you advance past the slice returned byfirst_slice(), the next call tofirst_slice()will return a new slice of bytes starting from the new front position of the view.

use bytesbuf::BytesView;

let len = bytes.len();

let mut slice_lengths = Vec::new();

while !bytes.is_empty() {

let slice = bytes.first_slice();

slice_lengths.push(slice.len());

// We have completed processing this slice. All we wanted was to know its length.

// We can now mark this slice as consumed, revealing the next slice for inspection.

bytes.advance(slice.len());

}

println!("Inspected a view over {len} bytes with slice lengths: {slice_lengths:?}");

To reuse a BytesView, clone it before consuming the contents. This is a cheap

zero-copy operation.

use bytesbuf::BytesView;

assert_eq!(bytes.len(), 16);

let mut bytes_clone = bytes.clone();

assert_eq!(bytes_clone.len(), 16);

// Consume 8 bytes from the front.

_ = bytes_clone.get_num_le::<u64>();

assert_eq!(bytes_clone.len(), 8);

// Operations on the clone have no effect on the original view.

assert_eq!(bytes.len(), 16);

Producing Byte Sequences

For creating a byte sequence, you first need some memory capacity to put the bytes into. This

means you need a memory provider, which is a type that implements the Memory trait.

Obtaining a memory provider is generally straightforward. Simply use the first matching option from the following list:

- If you are creating byte sequences for the purpose of submitting them to a specific

object of a known type (e.g. writing them to a

TcpConnection), the target type will typically implement theHasMemorytrait, which gives you a suitable memory provider instance viaHasMemory::memory(). Use this as the memory provider - this object will give you memory capacity with a configuration that is optimal for delivering bytes of data to that specific consumer (e.g.TcpConnection). - If you are creating byte sequences as part of usage-neutral data processing, obtain an

instance of a shared

GlobalPool. In a typical web application, the global memory pool is a service exposed by the application framework. In a different context (e.g. example or test code with no framework), you can create your own instance viaGlobalPool::new().

Once you have a memory provider, you can reserve memory from it by calling

Memory::reserve() on it. This returns a BytesBuf with at least the requested

number of bytes of memory capacity.

use bytesbuf::mem::Memory;

let memory = connection.memory();

let mut buf = memory.reserve(100);

Now that you have the memory capacity in a BytesBuf, you can fill the memory

capacity with bytes of data. Creating byte sequences in a BytesBuf is an

append-only process - you can only add data to the end of the buffered sequence.

There are many helper methods on BytesBuf for easily appending bytes to the buffer:

put_num_le::<T>()appends numbers. Big-endian/native-endian variants also exist.put_slice()appends a slice of bytes.put_byte()appends a single byte.put_byte_repeated()appends multiple repetitions of a byte.put_bytes()appends an existingBytesView.

use bytesbuf::mem::Memory;

let memory = connection.memory();

let mut buf = memory.reserve(100);

buf.put_num_be(1234_u64);

buf.put_num_be(5678_u64);

buf.put_slice(*b"Hello, world!");

If the helper methods are not sufficient, you can write contents directly into mutable byte slices using the fundamental methods that underpin the convenience methods:

first_unfilled_slice()returns a mutable slice of uninitialized bytes from the beginning of the buffer’s remaining capacity. The length of this slice is determined by the memory layout of the buffer and it may not contain all the capacity that has been reserved.advance()declares that a number of bytes at the beginning offirst_unfilled_slice()have been initialized with data and are no longer unused. This will mark these bytes as valid for consumption and advancefirst_unfilled_slice()to the next slice of unused memory capacity if the current slice has been completely filled.

See examples/bb_slice_by_slice_write.rs for an example of how to use these methods.

If you do not know exactly how much memory you need in advance, you can extend the BytesBuf

capacity on demand by calling BytesBuf::reserve. You can use remaining_capacity()

to identify how much unused memory capacity is available.

use bytesbuf::mem::Memory;

let memory = connection.memory();

let mut buf = memory.reserve(100);

// .. write some data into the buffer ..

// We discover that we need 80 additional bytes of memory! No problem.

buf.reserve(80, &memory);

// Remember that a memory provider can always provide more memory than requested.

assert!(buf.capacity() >= 100 + 80);

assert!(buf.remaining_capacity() >= 80);

When you have written your byte sequence into the memory capacity of the BytesBuf, you can consume

the data in the buffer as a BytesView.

use bytesbuf::mem::Memory;

let memory = connection.memory();

let mut buf = memory.reserve(100);

buf.put_num_be(1234_u64);

buf.put_num_be(5678_u64);

buf.put_slice(*b"Hello, world!");

let message = buf.consume_all();

This can be done piece by piece, and you can continue writing to the BytesBuf

after consuming some already written bytes.

use bytesbuf::mem::Memory;

let memory = connection.memory();

let mut buf = memory.reserve(100);

buf.put_num_be(1234_u64);

buf.put_num_be(5678_u64);

let first_8_bytes = buf.consume(8);

let second_8_bytes = buf.consume(8);

buf.put_slice(*b"Hello, world!");

let final_contents = buf.consume_all();

If you already have a BytesView that you want to write into a BytesBuf, call

BytesBuf::put_bytes. This is a highly efficient zero-copy operation

that reuses the memory capacity of the view you are appending.

use bytesbuf::mem::Memory;

let memory = connection.memory();

let mut header_builder = memory.reserve(16);

header_builder.put_num_be(1234_u64);

let header = header_builder.consume_all();

let mut buf = memory.reserve(128);

buf.put_bytes(header);

buf.put_slice(*b"Hello, world!");

Note that there is no requirement that the memory capacity of the buffer and the memory capacity of the view being appended come from the same memory provider. It is valid to mix and match memory from different providers, though this may disable some optimizations.

Implementing Types that Produce or Consume Byte Sequences

If you are implementing a type that produces or consumes byte sequences, you should

implement the HasMemory trait to make it possible for the caller to use optimally

configured memory when creating the byte sequences or buffers to use with your type.

Even if the implementation of your type today is not capable of taking advantage of

optimizations that depend on the memory configuration, it may be capable of doing so

in the future or may, today or in the future, pass the data to another type that

implements HasMemory, which can take advantage of memory optimizations.

Therefore, it is best to implement this trait on all types that consume byte sequences

via BytesView or produce byte sequences via BytesBuf.

The recommended implementation strategy for HasMemory is as follows:

- If your type always passes a

BytesVieworBytesBufto another type that implementsHasMemory, simply forward the memory provider from the other type. - If your type can take advantage of optimizations enabled by specific memory configurations, (e.g. because it uses operating system APIs that unlock better performance when the memory is appropriately configured), return a memory provider that performs the necessary configuration.

- If your type neither passes anything to another type that implements

HasMemorynor can take advantage of optimizations enabled by specific memory configurations, obtain an instance ofGlobalPoolas a dependency and return it as the memory provider.

Example of forwarding the memory provider (see examples/bb_has_memory_forwarding.rs

for full code):

use bytesbuf::mem::{HasMemory, MemoryShared};

impl HasMemory for ConnectionZeroCounter {

fn memory(&self) -> impl MemoryShared {

self.connection.memory()

}

}

Example of returning a memory provider that performs configuration for optimal memory (see

examples/bb_has_memory_optimizing.rs for full code):

use bytesbuf::mem::{CallbackMemory, HasMemory, MemoryShared};

/// Represents the optimal memory configuration for a UDP connection when reserving I/O memory.

const UDP_CONNECTION_OPTIMAL_MEMORY_CONFIGURATION: MemoryConfiguration = MemoryConfiguration {

requires_page_alignment: false,

zero_memory_on_release: false,

requires_registered_memory: true,

};

impl HasMemory for UdpConnection {

fn memory(&self) -> impl MemoryShared {

CallbackMemory::new({

// Cloning is cheap, as it is a service that shares resources between clones.

let io_context = self.io_context.clone();

move |min_len| {

io_context.reserve_io_memory(min_len, UDP_CONNECTION_OPTIMAL_MEMORY_CONFIGURATION)

}

})

}

}

Example of returning a global memory pool when the type is agnostic toward memory configuration

(see examples/bb_has_memory_global.rs for full code):

use bytesbuf::mem::{HasMemory, MemoryShared};

impl HasMemory for ChecksumCalculator {

fn memory(&self) -> impl MemoryShared {

// Cloning a memory provider is intended to be a cheap operation, reusing resources.

self.memory.clone()

}

}

It is generally expected that all types work with byte sequences using memory from any provider. It is true that in some cases this may be impossible (e.g. because you are interacting directly with a device driver that requires the data to be in a specific physical memory module) but these cases will be rare and must be explicitly documented.

If your type can take advantage of optimizations enabled by specific memory configurations, it needs to determine whether a byte sequence actually uses the desired memory configuration. This can be done by inspecting the provided byte sequence and the memory metadata it exposes. If the metadata indicates a suitable configuration, the optimal implementation can be used. Otherwise, the implementation can fall back to a generic implementation that works with any byte sequence.

Example of identifying whether a byte sequence uses the optimal memory configuration (see

examples/bb_optimal_path.rs for full code):

use bytesbuf::BytesView;

pub fn write(&mut self, message: BytesView) {

// We now need to identify whether the message actually uses memory that allows us to

// use the optimal I/O path. There is no requirement that the data passed to us contains

// only memory with our preferred configuration.

let use_optimal_path = message.iter_slice_metas().all(|meta| {

// If there is no metadata, the memory is not I/O memory.

meta.is_some_and(|meta| {

// If the type of metadata does not match the metadata

// exposed by the I/O memory provider, the memory is not I/O memory.

let Some(io_memory_configuration) = meta.downcast_ref::<MemoryConfiguration>()

else {

return false;

};

// If the memory is I/O memory but is not not pre-registered

// with the operating system, we cannot use the optimal path.

io_memory_configuration.requires_registered_memory

})

});

if use_optimal_path {

self.write_optimal(message);

} else {

self.write_fallback(message);

}

}

Note that there is no requirement that a byte sequence consists of homogeneous memory. Different parts of the byte sequence may come from different memory providers, so all chunks must be checked for compatibility.

Compatibility with the bytes Crate

The popular Bytes type from the bytes crate is often used in the Rust ecosystem to

represent simple byte buffers of consecutive bytes. For compatibility with this commonly used

type, this crate offers conversion methods to translate between BytesView and Bytes

when the bytes-compat Cargo feature is enabled:

BytesView::to_bytes()converts aBytesViewinto aBytesinstance. This is not always zero-copy because a byte sequence is not guaranteed to be consecutive in memory. You are discouraged from using this method in any performance-relevant logic path.BytesView::from(Bytes)orlet s: BytesView = bytes.into()converts aBytesinstance into aBytesView. This is an efficient zero-copy operation that reuses the memory of theBytesinstance.

Static Data

You may have static data in your logic, such as the names/prefixes of request/response headers:

const HEADER_PREFIX: &[u8] = b"Unix-Milliseconds: ";

Optimal processing of static data requires satisfying multiple requirements:

- We want zero-copy processing when consuming this data.

- We want to use memory that is optimally configured for the context in which the data is consumed (e.g. network connection, file, etc).

The standard pattern here is to use OnceLock to lazily initialize a BytesView from

the static data on first use, using memory from a memory provider that is optimal for the

intended usage.

use std::sync::OnceLock;

use bytesbuf::BytesView;

const HEADER_PREFIX: &[u8] = b"Unix-Milliseconds: ";

// We transform the static data into a BytesView on first use, via OnceLock.

//

// You are expected to reuse this variable as long as the context does not change.

// For example, it is typically fine to share this across multiple network connections

// because they all likely use the same memory configuration. However, writing to files

// may require a different memory configuration for optimality, so you would need a different

// `BytesView` for that. Such details will typically be documented in the API documentation

// of the type that consumes the `BytesView` (e.g. a network connection or a file writer).

let header_prefix = OnceLock::<BytesView>::new();

for _ in 0..10 {

let mut connection = Connection::accept();

// The static data is transformed into a BytesView on first use, using memory optimally configured

// for network connections. The underlying principle is that memory optimally configured for one network

// connection is likely also optimally configured for another network connection, enabling efficient reuse.

let header_prefix = header_prefix

.get_or_init(|| BytesView::copied_from_slice(HEADER_PREFIX, &connection.memory()));

// Now we can use the `header_prefix` BytesView in the connection logic.

// Cloning a BytesView is a cheap zero-copy operation.

connection.write(header_prefix.clone());

}

Different usages (e.g. file vs network) may require differently configured memory for optimal

performance, so you may need a different BytesView if the same static data is to be used

in different contexts.

Testing

For testing purposes, this crate exposes some special-purpose memory providers that are not optimized for real-world usage but may be useful to test corner cases of byte sequence processing in your code.

See the mem::testing module for details (requires test-util Cargo feature).

This crate was developed as part of The Oxidizer Project. Browse this crate's source code.