meshx

| Crates.io | meshx |

| lib.rs | meshx |

| version | 0.7.0 |

| created_at | 2021-11-11 18:56:44.537558+00 |

| updated_at | 2025-04-16 07:10:36.461077+00 |

| description | A mesh eXchange library with conversion utilities for popular mesh formats. |

| homepage | https://github.com/elrnv/meshx |

| repository | https://github.com/elrnv/meshx |

| max_upload_size | |

| id | 480331 |

| size | 1,517,841 |

documentation

README

meshx

A mesh exchange library for providing convenient conversion utilities between popular mesh formats.

Disclamer: meshx is still in the early stage of its development and using it in a production

environment is not recommended. The meshx API is not stable and is subject to change.

Overview

This library is designed to simplify interoperability between different 3D applications using mesh data

structures. meshx also provides common mesh types and related traits to work with attributes.

Different components of this library can be useful in different circumstances. To name a few use

cases, meshx can be used to

- import or export meshes from files,

- build plugins for 3D applications

- store untyped mesh data for long term use

- build a visualization tool to display mesh attributes

- build new mesh types specific to your application using a familiar API.

For more details please refer to the

documentation.

Quick Tutorial

Here we'll explore different uses of meshx.

Building meshes

This library includes a few concrete built-in mesh types like TriMesh for triangle meshes,

PolyMesh for polygonal meshes and TetMesh for tetrahedral meshes often used in finite element

simulations. Let's create a simple triangle mesh consisting of two triangles to start:

use meshx::TriMesh;

// Four corners of a [0,0]x[1,1] square in the xy-plane.

let vertices = vec![

[0.0f64, 0.0, 0.0],

[1.0, 0.0, 0.0],

[0.0, 1.0, 0.0],

[1.0, 1.0, 0.0],

];

// Two triangles making up a square.

let indices = vec![[0, 1, 2], [1, 3, 2]];

// Create the triangle mesh

// NOTE: TriMesh is generic over position type, so you need to

// specify the specific float type somewhere.

let trimesh = TriMesh::new(vertices, indices);

Simple count queries

Our new triangle mesh interprets the passed vertices and inidices as mesh data, which gives us information about the mesh. We can now ask for relevant quantities as follows:

use meshx::topology:*; // Prepare to get topology information.

println!("number of vertices: {}", mesh.num_vertices());

println!("number of faces: {}", mesh.num_faces());

println!("number of face-edges: {}", mesh.num_face_edges());

println!("number of face-vertices: {}", mesh.num_face_vertices());

which prints

number of vertices: 4

number of faces: 2

number of face-edges: 6

number of face-vertices: 6

In the next section we will explore what is meant by face-edges and face-vertices here.

Topology queries

Our simple triangle mesh is represented by 2 triangles, each pointing to 3 vertices on our array of 4 vertices. This connectivity relationship solely defines a triangle mesh. We can visualize our particular example in ASCII with vertices numbered outside and triangle indices inside:

2 3

+--------+

|\ |

| \ 1 |

| \ |

| \ |

| \ |

| \ |

| 0 \ |

| \|

y +--------+

^ 0 1

|

+--> x

If we number each of the triangle indices in a row, we will come up with a total of 6 indices.

These are called face-vertices in meshx. For our example, we write linear face-vertex indices

inside the triangles:

2 3

+--------+

|\5 4|

|2\ |

| \ |

| \ |

| \ |

| \ |

| \3|

|0 1\|

y +--------+

^ 0 1

|

+--> x

In turn face-edges are the directed edges inside each face that start at each of t he face-vertices in a counter-clockwise direction. For example the first face-edge correspondes to the 0->1 edge in the first triangle at index 0.

This structure can be easily generalized to other meshes following a similar naming convention. We

use the words vertex, edge, face and cell to represent 0, 1, 2, and 3 dimensional elements respectively.

When face and cell types are mixed like in unstructured meshes (e.g. the Mesh type), we refer to

them simply as cells to be consistent with other libraries like VTK.

Knowing this we can query a particular face, face-edge, face-vertex or vertex in our triangle mesh:

// Get triangle indices:

println!("face 1: {:?}", mesh.face(1));

// Face-edge topology:

// These functions are provided by the FaceEdge trait.

println!("face-edge index of edge 2 on face 1: {:?}", mesh.face_edge(1, 2));

println!("edge index of face-edge 5: {:?}", mesh.edge(5));

println!("edge index of edge 2 on face 1: {:?}", mesh.face_to_edge(1, 2));

// Face-vertex topology:

// These functions are provided by the FaceVertex trait.

println!("face-vertex index of vertex 1 on face 0: {:?}", mesh.face_vertex(0, 1));

println!("vertex index of face-vertex 1: {:?}", mesh.vertex(1));

println!("vertex index of vertex 1 on face 0: {:?}", mesh.face_vertex(0, 1));

which outputs:

face 1: [1, 3, 2]

face-edge index of edge 2 on face 1: Some(FaceEdgeIndex(5))

edge index of face-edge 5: EdgeIndex(2)

edge index of edge 2 on face 1: Some(EdgeIndex(2))

face-vertex index of vertex 1 on face 0: Some(FaceVertexIndex(1))

vertex index of face-vertex 1: VertexIndex(1)

vertex index of vertex 1 on face 0: Some(FaceVertexIndex(1))

For now the topology query functions here return an Option when given an index within an element,

since these are not typed. In that case None is returned for out-of-bounds indices. Typed indices

(e.g. EdgeIndex, FaceVertexIndex) are expected to be correctly bounded. If an incorrect typed

index is given, the function will panic.

FaceVertex topology is commonly used to assign uv or texture coordinates to meshes.

FaceEdge topology can be used to define a

half-edge interface on meshes.

Attributes

When working with meshes in 3D applications, it is essential to be able to load and store values for different elements of the mesh. Each element (vertex, edge, face, or cell) or topology element (e.g. face-edge, face-vertex) supported by a mesh can store values of any type associated with that element.

For instance we can store vertex normals at vertices, or texture coordinates on face-vertices to indicate where on a texture to map each triangle.

Let's add some associated vectors to the vertices on our mesh pointing up (+z) and away from the mesh. This can represent physical quantities like forces or velocities, or normals used for shading.

use meshx::attrib::*;

let mut mesh = mesh; // Make mesh mutable.

let vectors = vec![

[-1.0, -1.0, 1.0],

[1.0, -1.0, 1.0],

[-1.0, 1.0, 1.0],

[1.0, 1.0, 1.0],

];

mesh.insert_attrib_data::<[f32; 3], VertexIndex>("up_and_away", vectors).unwrap();

meshx supports many ways of manipulating attributes, down to destructuring the mesh to expose

the structures that store these attributes. For more details see the

attrib module and the

attrib::Attrib trait.

IO: loading and saving meshes

Using the io module we can load and store meshes. To save our triangle mesh to a file, we can

simply call save_trimesh specifying a path:

meshx::io::save_trimesh(&mesh, "tests/artifacts/tutorial_trimesh.vtk").unwrap();

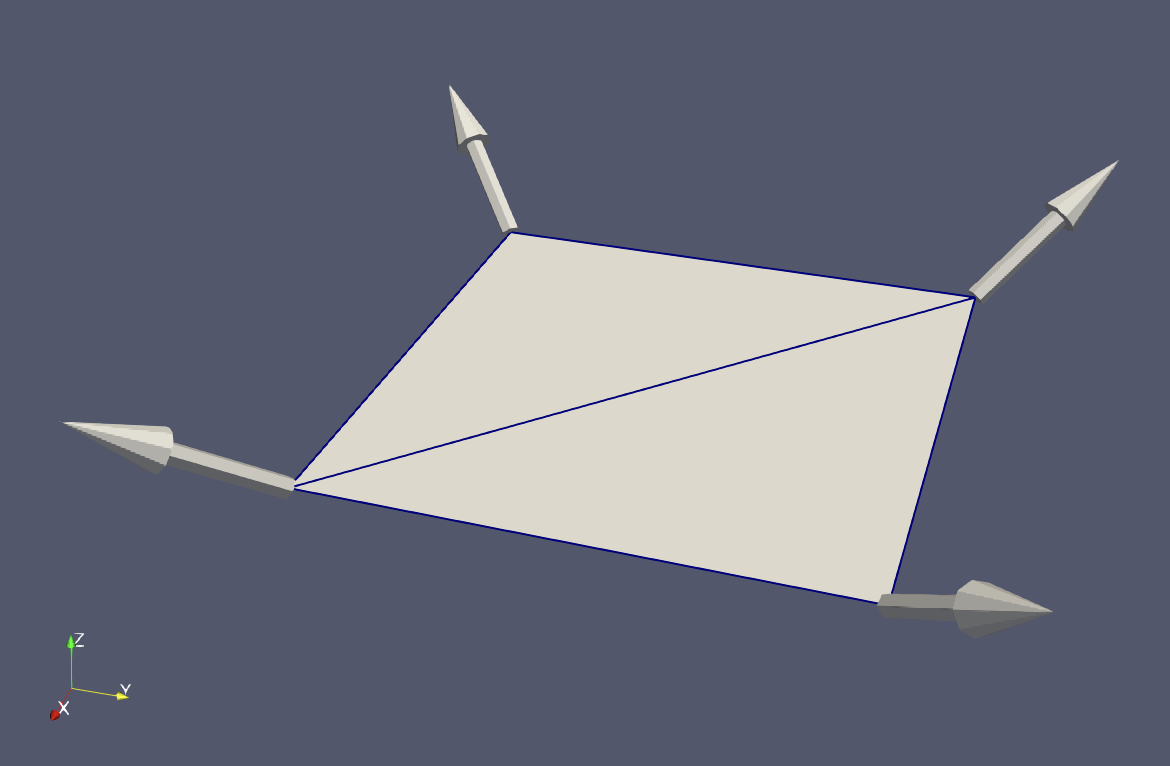

This can then be loaded from another application like ParaView. Here is our mesh with the

associated vectors shown as arrows:

We can also load this file back using load_trimesh.

let loaded_mesh = meshx::io::load_trimesh("tests/artifacts/tutorial_trimesh.vtk").unwrap();

See the io module for supported formats.

Since the vertex positions and attributes happen to be exactly representable with floats, we can expect the two meshes to be identical:

assert_eq!(mesh, loaded_mesh);

Although this may not always be true in general when meshes can cache attribute data.

Conclusion

In this short tutorial we have covered

- Building a mesh

- Getting element and connection counts on a mesh with

num_*functions - Accessing various indices associated with a mesh

- Inserting attribute data on mesh vertices

- Saving and loading a mesh to and from a file.

The code in this tutorial is available in examples/tutorial.rs and can be

run with

$ cargo run --example tutorial

For more details on the API, please consult the documentation.

License

This repository is licensed under either of

- Apache License, Version 2.0, (LICENSE-APACHE or https://www.apache.org/licenses/LICENSE-2.0)

- MIT License (LICENSE-MIT or https://opensource.org/licenses/MIT)

at your option.