tfmt

| Crates.io | tfmt |

| lib.rs | tfmt |

| version | 0.4.0 |

| created_at | 2024-04-17 06:42:16.886897+00 |

| updated_at | 2024-04-17 06:42:16.886897+00 |

| description | A tiny, fast and panic-free alternative to `core::fmt` |

| homepage | |

| repository | https://github.com/simsys/tfmt |

| max_upload_size | |

| id | 1211087 |

| size | 91,612 |

documentation

README

A tiny, fast and panic-free alternative to core::fmt

The basis for the development of tfmt is japaric's ufmt. All the main ideas and concepts come from there. However, the author makes it clear that the representation of floating point numbers and padding is not the focus of the implementation. For some projects, it is precisely these points that are important.

Design Goals

- Optimised for size and speed for small embedded systems

- Usable during development

Debugand runtimeDisplay - No panicking branches in generated code when optimised

- It should be easy to integrate additional data types

Features

- String conversation and formatting options for the following data types included

- u8, u16, u32, u64, u128, usize

- i8, i16, i32, i64, i128, isize

- bool, str, char

- f32, f64

- [

#[derive(uDebug)]][macro@derive] uDebuganduDisplaytraits like [core::fmt::Debug] and [core::fmt::Display]- [uDisplayPadded] trait for formatted outputs

- [uDisplayFormatted] trait for complex formatted outputs

- [uformat] macro to simply generating of strings

Restrictions

tfmt offers significantly less functionality than core::fmt. For example:

- No named arguments

- No exponential representation of float numbers

- Restricted number range of float numbers (see

tests/float.rs) - Arrays may have a maximum of 32 elements [

#[derive(uDebug)]][macro@derive] - Tuples can have a maximum of 12 elements [

#[derive(uDebug)]][macro@derive] - Unions are not supported [

#[derive(uDebug)]][macro@derive]

Examples

Format Standard Rust Types

use tfmt::uformat;

assert_eq!(

uformat!(100, "The answer to {} is {}", "everything", 42).unwrap().as_str(),

"The answer to everything is 42"

);

assert_eq!("4711", uformat!(100, "{}", 4711).unwrap().as_str());

assert_eq!("00004711", uformat!(100, "{:08}", 4711).unwrap().as_str());

assert_eq!(" -4711", uformat!(100, "{:8}", -4711).unwrap().as_str());

assert_eq!("-4711 ", uformat!(100, "{:<8}", -4711).unwrap().as_str());

assert_eq!(" 4711 ", uformat!(100, "{:^8}", 4711).unwrap().as_str());

assert_eq!("1ab4", uformat!(100, "{:x}", 0x1ab4).unwrap().as_str());

assert_eq!(" 1AB4", uformat!(100, "{:8X}", 0x1ab4).unwrap().as_str());

assert_eq!("0x1ab4", uformat!(100, "{:#x}", 0x1ab4).unwrap().as_str());

assert_eq!("00001ab4", uformat!(100, "{:08x}", 0x1ab4).unwrap().as_str());

assert_eq!("0x001ab4", uformat!(100, "{:#08x}", 0x1ab4).unwrap().as_str());

assert_eq!("0b010010", uformat!(100, "{:#08b}", 18).unwrap().as_str());

assert_eq!("0o011147", uformat!(100, "{:#08o}", 4711).unwrap().as_str());

assert_eq!("3.14", uformat!(100, "{:.2}", 3.14).unwrap().as_str());

assert_eq!(" 3.14", uformat!(100, "{:8.2}", 3.14).unwrap().as_str());

assert_eq!("3.14 ", uformat!(100, "{:<8.2}", 3.14).unwrap().as_str());

assert_eq!(" 3.14 ", uformat!(100, "{:^8.2}", 3.14).unwrap().as_str());

assert_eq!("00003.14", uformat!(100, "{:08.2}", 3.14).unwrap().as_str());

assert_eq!("hello", uformat!(100, "{}", "hello").unwrap().as_str());

assert_eq!(" true ", uformat!(100, "{:^8}", true).unwrap().as_str());

assert_eq!("c ", uformat!(100, "{:<8}", 'c').unwrap().as_str());

Using Derive uDebug

use tfmt::{uformat, derive::uDebug};

#[derive(uDebug)]

struct S1Struct {

f: f32,

b: bool,

sub: S2Struct,

}

#[derive(uDebug)]

struct S2Struct {

tup: (i16, f32),

end: [u16; 2],

}

let s2 = S2Struct { tup: (-4711, 3.14), end: [1, 2] };

let s1 = S1Struct { f: 1.0, b: true, sub: s2 };

let s = uformat!(200, "{:#?}", &s1).unwrap();

assert_eq!(

s.as_str(),

"S1Struct {

f: 1.000,

b: true,

sub: S2Struct {

tup: (

-4711,

3.140,

),

end: [

1,

2,

],

},

}");

let s = uformat!(200, "{:?}", &s1).unwrap();

assert_eq!(

s.as_str(),

"S1Struct { f: 1.000, b: true, sub: S2Struct { tup: (-4711, 3.140), end: [1, 2] } }"

);

Format Your own Structures

use tfmt::{uformat, uDisplayPadded, uWrite, Formatter, Padding};

struct EmailAddress {

fname: &'static str,

lname: &'static str,

email: &'static str,

}

impl uDisplayPadded for EmailAddress{

fn fmt_padded<W>(

&self,

fmt: &mut Formatter<'_, W>,

padding: Padding,

pad_char: char,

) -> Result<(), W::Error>

where

W: uWrite + ?Sized

{

let s = uformat!(128, "{}.{} <{}>", self.fname, self.lname, self.email).unwrap();

fmt.write_padded(s.as_str(), pad_char, padding)

}

}

let email = EmailAddress { fname: "Graydon", lname: "Hoare", email: "graydon@pobox.com"};

let s = uformat!(100, "'{:_^50}'", email).unwrap();

assert_eq!(

s.as_str(),

"'________Graydon.Hoare <graydon@pobox.com>_________'"

);

Technical Notes

Performance

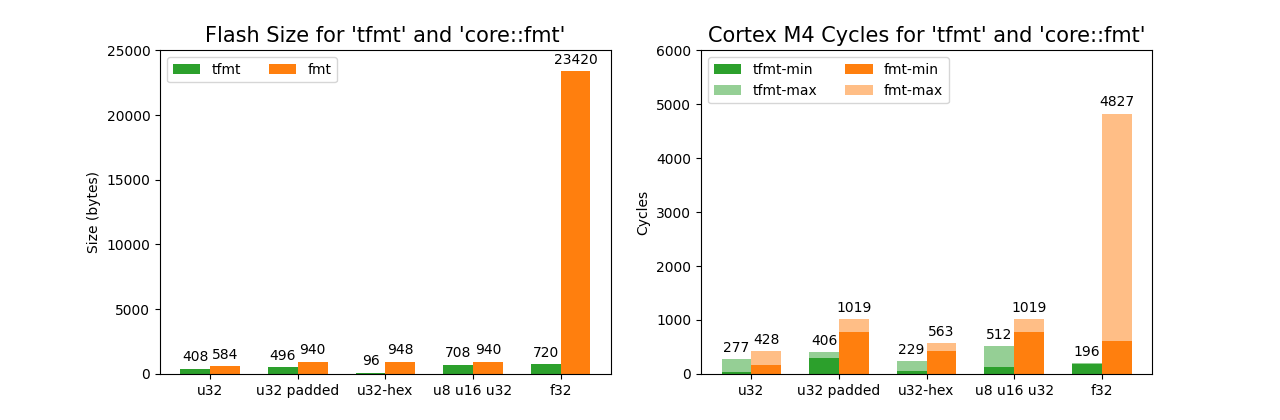

The use of micro-benchmarks is usually problematic. Nevertheless, the trends can be recognised

very well. The following table shows a comparison of tfmt with core::fmt using a few examples.

tfmt is significantly smaller and also much faster than core::fmt. Another difference is that

tfmt does not contain a panicking branch. This can be an important difference for embedded

systems. The high memory requirement of core::fmt in connection with floats is astonishing. The

strong fluctuations in the required cycles are also surprising.

The sources for generating the data and the visualisation can be found in the tests/size

directory.

| Name | Crate | Size | Cycles_min | Cycles_max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| u32 | tfmt | 408 | 34 | 277 |

| u32 | fmt | 584 | 166 | 428 |

| u32 padded | tfmt | 496 | 284 | 406 |

| u32 padded | fmt | 940 | 770 | 1019 |

| u32-hex | tfmt | 128 | 125 | 237 |

| u32-hex | fmt | 948 | 422 | 563 |

| u8 u16 u32 | tfmt | 708 | 118 | 512 |

| u8 u16 u32 | fmt | 940 | 770 | 1019 |

| f32 | tfmt | 720 | 189 | 196 |

| f32 | fmt | 23420 | 1049 | 4799 |

The contents of the table are shown graphically below:

Use of unsafe

Unsafe is used in several places in the code. Careful consideration has been given to whether this is necessary and safe. Unsafe is useful in the following situations:

- Some cycles can be saved if buffers that are guaranteed to be written later are not initialised initially. In simple situations, the compiler sees this and omits the initialisation itself. In more complex structures, however, it is not able to do this (src/float.rs).

- To avoid panicking branches, arrays are usually accessed with pointers. Either the context ensures that this works or it is checked.

- Bytes buffer is converted to str without checking for UTF8 compatibility. This is safe because the buffer was previously written with defined UTF8-compliant characters.

All positions have been commented accordingly.

License

All source code (including code snippets) is licensed under either of

-

Apache License, Version 2.0 (LICENSE-APACHE or https://www.apache.org/licenses/LICENSE-2.0)

-

MIT license (LICENSE-MIT or https://opensource.org/licenses/MIT)

at your option.

Contribution

Unless you explicitly state otherwise, any contribution intentionally submitted for inclusion in the work by you, as defined in the Apache-2.0 license, shall be licensed as above, without any additional terms or conditions.